APA – The Engineered Wood Association is the nonprofit trade association of the U.S. and Canadian engineered wood products industry. Based in Tacoma, Washington, the Association is comprised of and represents manufacturers of structural plywood, oriented strand board (OSB), cross-laminated timber, glued laminated (glulam) timber, wood I-joists, and laminated veneer lumber (LVL).

APA – The Engineered Wood Association is the nonprofit trade association of the U.S. and Canadian engineered wood products industry. Based in Tacoma, Washington, the Association is comprised of and represents manufacturers of structural plywood, oriented strand board (OSB), cross-laminated timber, glued laminated (glulam) timber, wood I-joists, and laminated veneer lumber (LVL).

APA was founded in 1933 as the Douglas Fir Plywood Association to advance the interests of the burgeoning Pacific Northwest plywood industry. Adhesive and technology improvements eventually led to the manufacture of structural plywood from Southern pine and other species, and in 1964 the Association changed its name to American Plywood Association (APA) to reflect the national scope of its growing membership.

The Association’s membership expanded again in the early 1980s with the introduction of oriented strand board (OSB), a product the Association helped bring to market through development of new panel performance standards. A decade later, APA accommodated manufacturers of non-panel engineered wood products, such as glulam timber, wood I-joists and laminated veneer lumber.

To better reflect the broadening product mix and geographic range of its membership, the Association changed its name again in 1994 to APA – The Engineered Wood Association. The acronym “APA” was retained in the name because it was so widely known and respected in the marketplace.

History of Plywood

Ancient Origins of Plywood

Archeologists have found traces of laminated wood in the tombs of the Egyptian pharaohs. A thousand years ago, the Chinese shaved wood and glued it together for use in furniture. The English and French are reported to have worked wood on the general principle of plywood in the 17th and 18th centuries. And historians credit Czarist Russia for having made forms of plywood prior to the 20th century as well. Early modern-era plywood was typically made from decorative hardwoods and most commonly used in the manufacture of household items, such as cabinets, chests, desk tops and doors. Construction plywood made from softwood species did not appear on the scene until the 20th century.

Plywood Patented, Then Forgotten

The first patent for what could be called plywood was issued December 26, 1865, to John K. Mayo of New York City. A re-issue of that patent, dated August 18, 1868, described Mayo’s development as follows: “The invention consists in cementing or otherwise fastening together a number of these scales of sheets, with the grain of the successive pieces, or some of them, running crosswise or diversely from that of the others…” Mayo may have had a vision, but apparently not much business sense, since history does not record that he ever capitalized on his patents.

1905: An Industry is Born

1905: An Industry is Born

In 1905, the city of Portland, Oregon was getting ready to host a World’s Fair as part of the 100th anniversary celebration of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Several local businesses were asked to prepare exhibits for the event, including Portland Manufacturing Company, a small wooden box factory in the St. Johns district of the city. Part owner and plant manager Gustav Carlson decided to laminate wood panels from a variety of Pacific Northwest softwoods. Using paint brushes as glue spreaders and house jacks as presses, several panels were laid up for display. Called “3-ply veneer work,” the product created considerable interest among fairgoers, including several door, cabinet and trunk manufacturers who then placed orders. By 1907, Portland Manufacturing had installed an automatic glue spreader and a sectional hand press. Production soared to 420 panels a day. And an industry was born.

From Doors to Running Boards: The First Plywood Markets

During its first 15 years the softwood plywood industry relied primarily on a single market—door panels. But in 1920, “super salesman” Gus Bartells of Elliott Bay Plywood in Seattle began generating customers in the automobile industry. Bartells had earlier established the first plywood dealerships around the country, and was equally successful in getting car manufacturers to use plywood for running boards. The market took off and the industry enjoyed steady growth during the Jazz Age. By 1929, there were 17 plywood mills in the Pacific Northwest and production reached a record 358 million square feet (3/8-inch basis).

A Technological Breakthrough: Waterproof Adhesive

A Technological Breakthrough: Waterproof Adhesive

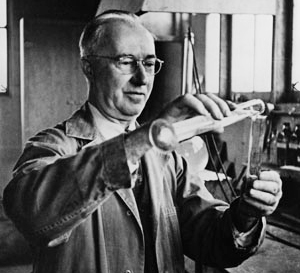

Lack of a waterproof adhesive that would make plywood suitable for exterior exposure eventually led automobile manufacturers to switch from plywood to more durable metal running boards. A breakthrough came in 1934 when Dr. James Nevin, a chemist at Harbor Plywood Corporation in Aberdeen, Washington, finally developed a fully waterproof adhesive. This technology advancement had the potential to open up significant new markets. But the industry remained fragmented. Product quality and grading systems varied widely from mill to mill. Individual companies didn’t have the technical or in most cases marketing resources to research, develop and promote new uses for plywood. The industry looked for help from its newly formed trade association, the Douglas Fir Plywood Association.

Founding of the Douglas Fir Plywood Association

Several failed attempts to establish a plywood association were made in the early years of the industry. Finally, on May 16, 1933, several fir plywood manufacturers met at the old Portland Hotel to discuss the advisability of adopting certain trade practices before the industry would be forced to do so under the Depression-era National Recovery Act. The act was later declared unconstitutional but for a time put pressure on the plywood industry to organize. A month of negotiations followed and on June 13, 1933, the Douglas Fir Plywood Association held its first regular meeting at the Winthrop Hotel in Tacoma, Washington. The new association struggled until, in 1938, it hired a legendary business development guru, W. E. “Diff” Difford.

Standardization and Improved Quality Testing Boost Sales

The Douglas Fir Plywood Association was among the first to take advantage of a 1938 law that permitted registration of industrywide trademarks, which allowed plywood to be promoted as a standardized commodity rather than by individual brand names. That same year, FHA accepted exterior plywood, based in part on a new Commercial Standard that included performance tests for both interior and exterior plywood. These developments helped clear the way for more successful promotion of plywood’s benefits to the construction industry. “Dri-Bilt With Plywood” became a familiar advertising slogan. More than a million low-cost Dri-Bilt homes were constructed featuring DFPA-trademarked PlyScord subfloors and sheathing, PlyWall ceilings and walls, PlyPanel built-ins, and PlyShield siding. In 1940, the association sponsored “The House in the Sun,” the first of many plywood demonstration houses. Plywood’s growing reputation as a strong and durable construction material was soon put to the extreme test by war.

Plywood Goes to War

Plywood Goes to War

World War II was a proving ground for plywood. The product was declared an essential war material and production and distribution came under strict controls. The industry’s war-time mills—by this time numbering about 30—produced between 1.2 and 1.8 billion square feet annually. Plywood barracks sprung up everywhere. The Navy patrolled the Pacific in plywood PT boats. The Air Force flew reconnaissance missions in plywood gliders. And the Army crossed the Rhine River in plywood assault boats. There were thousands of war accessories made of plywood—from crating for machinery parts, to huts for the famed Seabees in the South Pacific, to lifeboats on hundreds of ships that kept supply lines open in the Atlantic and Pacific.

The Post-War Boom

With the war ended, the industry geared up to meet growing demand in the booming post-war economy. In 1944, the industry’s 30 mills produced 1.4 billion square feet of plywood. By 1954, the industry had grown to 101 mills and production approached 4 billion square feet. That same year, the Stanford Research Institute predicted that demand for plywood would rise to 7 billion feet by 1975—21 years into the future. Although some were skeptical, production rocketed to 7.8 billion feet in just five years, and by 1975 U.S. production alone exceeded 16 billion square feet, more than double the forecast.

Plywood Goes North

With its rich forest resources, it was only natural that Canada should join what eventually would become a truly North American plywood industry. The first Canadian plywood was produced in 1913 at Fraser Mills, New Westminster, British Columbia, but it wasn’t until 1935 that a second mill was opened—by the H.R. MacMillan Company. In 1950, five Canadian companies founded the Plywood Manufacturers Association of British Columbia (PMBC), which eventually evolved into the Canadian Plywood Association (CANPLY). The Canadian Standards Association published the first Canadian Plywood Standard in 1953 based on specifications developed by PMBC.

The Rise of Southern Pine

For more than a half century the softwood plywood industry was located exclusively in the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia using the region’s vast supply of Douglas fir. Until mid-century, it was not known how to effectively glue together veneer from softwood species grown in other regions. But research and development efforts changed that in the late 1950s and early 60s, and in 1964 Georgia-Pacific Corporation opened the first southern pine plywood mill, in Fordyce, Arkansas. The Douglas Fir Plywood Association changed its name that same year to reflect the fact that the plywood industry was now national in scope. Today, some two-thirds of all U.S. plywood is produced in the South.

Technology Marches On

Technology Marches On

Plywood is often called the original engineered wood product because it was one of the first to be made by bonding together cut or refashioned pieces of wood to form a larger and integral composite unit stronger and stiffer than the sum of its parts. Cross-laminating layers of wood veneer actually improve upon the inherent structural advantages of wood by distributing along-the-grain strength of wood in both directions. This idea of “reconstituting” wood fiber to produce better-than-wood building materials has led in more recent times to a technological revolution and the rise of a whole new engineered wood products industry. In the late 1970s and early 80s, for example, the plywood principle gave rise to what today is a worldwide oriented strand board, or OSB, industry. Instead of solid sheets of veneer, OSB is made of small wood strands that are glued together in cross-laminated layers. Other engineered wood products today include wood I-joists, glued laminated timber, laminated veneer lumber, and oriented strand lumber. These products not only yield superior performance properties, but also make better use of precious forest resources. And it all began with plywood.

History of Glulam

Glulam was first used in Europe in the early 1890s. A 1901 patent from Switzerland signaled the true beginning of glued laminated timber construction. One of the first glulam structures erected in the US was a research laboratory at the USDA Forest Products Laboratory in Madison, Wisconsin. The structure was erected in 1934 and is still in service today.

A significant development in the glulam industry was the introduction of fully water-resistant phenol-resorcinol adhesives in 1942. This allowed glulam to be used in exposed exterior environments without concern of glueline degradation.

The first US manufacturing standard for glulam was Commercial Standard CS253-63, which was published by the Department of Commerce in 1963. The most recent standard is ANSI Standard A190.1.

Wood I-joists and Rim Board®

Originally commercialized by the Trus Joist Corporation (now a Weyerhaeuser company) in the 1960s, engineered wood I-joists owe their beginning, at least in part, to a publication developed by the Douglas Fir Plywood Association, (the precursor to APA – The Engineered Wood Association) in 1959 entitled DFPA Specification BB-8, Design of Plywood Beams. This specification, later published as Plywood Design Specification Supplement 2, Design and Fabrication of Glued Plywood-Lumber Beams, outlined the original design procedures that ultimately provided the basis for current design recommendations.

The first universally recognized standard for wood I-joists was, and still is, ASTM D5055, Standard Specification for Establishing and Monitoring Structural Capacities of Prefabricated Wood I-Joists. This consensus standard provides guidelines for the evaluation of mechanical properties, physical properties, and quality of wood I-joists and is the current common testing standard for I-joists. However, since ASTM D5055 does not specify required levels of performance, individual manufacturers of I-joists generally have their own proprietary company standards that govern the everyday production practice for their products. As the history of other building materials such as plywood and oriented strand board (OSB) has shown, some degree of standardization of the industry is inevitable. Also inevitable is that along with standardization will come greater manufacturing efficiencies and greater use in construction.

To fill this need for standard performance levels, APA, in conjunction with several I-joist manufacturers, has developed performance-based standards for performance-rated wood I-joist products. The first such APA performance standard is for the use of wood I-joists in residential floors, designated as PRI-400, although roof tables and details have also been developed for the PRI-400 joists. It should be noted that this is a voluntary standard and not all I-joist manufacturers have chosen to produce PRI-400 products.